THE WORLD'S MOST POPULAR PLANES: TIMEBOMBS?

![]()

Boeing 737. Airbus 320. If you're like most people, these words mean absolutely nothing to you. Perhaps, if you're a business or otherwise frequent traveler, you may have flown on one of these. As a matter of fact, the 737 and A320 are two of the most popular airliners in the world. But, why the story? Why the "Timebomb" accusation? Well, it turns out that each of these planes has a fatal flaw.

Not to scare anyone, but both the Boeing 737 and Airbus 320 aircraft do have rather glaring problems with themselves. Although these problems probably won't result in anything happening to you, you must know exactly what is wrong with these aircraft.

Many airlines use the 737 and A320 as short-range passenger transports. The 737 is frequently used in the United States, and the A320 is more commonly used abroad in short-distance flights. Nevertheless, some U.S. airlines do own A320s and many foreign carriers use 737s. As one can see below, the 737 and A320 are quite similar aircraft.

Above: The Boeing 737

Above: The Airbus 319 (a part of the A320 family). Not much difference, eh?

So, what are these doomsday possibilities? Again, remember, they are not very likely to manifest themselves. Here are the problems:

The Boeing 737: Rudder Problems

Well, first of all, before you start panicking about "rudder problems," perhaps you should know what the rudder is and exactly what the 737's problem is with its rudder:

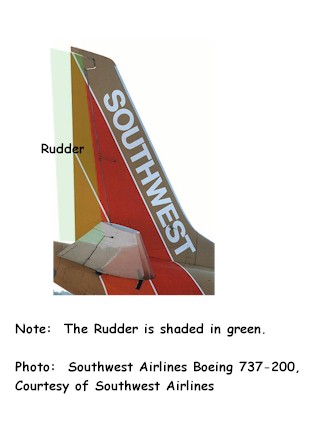

Figure 1: The rudder, or horizontal stabilizer. This flap can move side-to-side and causes the plane to yaw, or rotate. The rudder is located on the tail of the aircraft, as shown below:

Enough suspense, what's up with the 737's rudder? Well, essentially all other commercial aircraft have two hydraulic (air-operated) pumps that move the rudder left and right. If the main pump fails, a reserve pump will take over and help the pilot control the rudder. However, the 737 has only one hydraulic pump. This means that if this pump fails, the rudder will stop moving. If the rudder is turned when the pump fails, it will be stuck in that turned position, causing the plane to continuously yaw and even roll over. The 737's pump has even been said to have a "mind of its own," occasionally deploying and freezing the rudder by itself. The pilot cannot correct this undesired rudder position because the hydraulic pump controlling the rudder does not work and does not have a backup.

So, how is your safety compromised because of this? Many times, the rollover that occurs because of excess yaw is unrecoverable, or, in other words, the pilot cannot stabilize the plane back into normal flying position after the rollover has occured. This may lead to a crash, and such events have happened at least twice in the United States.

In one of these events, United Airlines Flight 445 at Colorado Springs, Colorado, a rudder problem was suspected as the cause of this Boeing 737-200 crashing. All 5 crew members and 20 passengers aboard were killed.

In another suspected rudder failure of the 737, USAir (Now USAirways) flight 427 rolled and crashed on approach to the Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania Airport. An uncommanded rudder deployment was suspected to have caused this accident, according to the NTSB. The incredibly strange thing is, I was on this exact same flight two weeks before the incident!

You probably shouldn't panic, though. Despite these two crashes, there are over 2,000 737s around the world flying tens of thousands of passengers everywhere. The 737 as a model line carries more flights than any other airliner ever built. Therefore, two crashes because of a certain problem is probably statistically insignificant when looking at the large picture of air safety. Nevertheless, this story appears to be something that should be looked at, and the NTSB is looking into making Boeing recall its defective 737s in batches.

![]()

In the other corner of disaster, the Airbus 320!

First came the Airbus 319, then the Airbus 320; these are both competitors to the Boeing 737. However, what's the problem here? You see, the A320 is fly-by-wire, which means that all of the control manipulations done by the pilot are converted into electrical signals and then reprocessed to produce mechanical movement in the aircraft's control systems. Essentially, if you are flying the A320, you are trusting a computer with your flight.

This trust proved disasterous one morning in 1988 at the Mulhouse-Habsheim airport in France. After setting the aircraft for takeoff, the crew lifted off from the airport. After going only about 100 feet into the air, the plane begin to descend as its computer system thought that the plane was landing, not taking off! The Airbus 320 then crashed into the woods immediately in front of the runway, creating a large explosion and killing 3 of the 136 passengers on board. This incident was especially embarassing to Airbus since it occured at an air show, in front of thousands of spectators. Fortunately, this problem has not reared its head again since 1988, despite the millions of flights A320 aircraft have been on. Nevertheless, it is still a risk (no matter how miniscule) to fly on the A320. No official government investigation has been undertaken on the A320 as of now.

![]()

Source of accident information: Airsafe Industries & Insurance

Investigation Information:

Dunham, A.G. "The Crash of USAir 427: Boeing Blamed In 737 Crashes" (The Mining Company Air Travel Channel).

Malnic, Eric. "Causes Of Similar 737 Jet Crashes Still a Mystery" Los Angeles Times. 18 October 1994, pp A1+.

Photos of United 737 and A319 courtesy of United Airlines.

Background Picture: Southwest Airlines Boeing 737 "Shamu" paint scheme. Photo courtesy Southwest Airlines.

![]()